The birth of modern democracy in the heart of Europe

The "Swiss Revolution" brought democracy to Switzerland. It was an uprising against the aristocracy – and the beginning of a long journey that the country could only complete with foreign help.

On a spring day in 1798, Peter Ochs of Basel declared the birth of the Helvetic Republic from a balcony of the Aarau city hall. There was great rejoicing on the streets because this marked the liberation of the central territories from their Bernese masters.

Ochs had been commissioned by the French government to draft a constitution to create a unified state. In this document, the enlightened reformer justified the division of powers between law-making, executive, and judicial authorities – the first time this was done on a constitutional level.

The Helvetic Republic only lasted from 1798 to 1803. It revolved completely around the French policy of the time, which envisaged creating sister republics – even if it required force. It depended on the economically powerful but politically disenfranchised citizens living under the Ancien Regime. But it failed because of the ruling aristocrats in the guilds, patrician houses and rural communities.

This series in several parts is tailored for our author: Claude Longchamp’s expertise makes him the man who can bring alive the places where important things happened.

Longchamp was a founder of the research institute gfs.bern and is the most experienced political analyst in Switzerland. He is also a historian. Combining these disciplines, Longchamp has for many years given highly acclaimed historic tours of Bern and other sites.

“Longchamp performs democracy,” was one journalist’s headline on a report about a city tour.

This multimedia series, which the author is producing exclusively for SWI swissinfo.ch, doesn’t concentrate on cities – instead its focus is on important places.

He also posts regular contributions on FacebookExternal link, Instagram External linkund TwitterExternal link.

It was, however, a breakthrough on the path to democracy. Shortly afterwards, in 1803 and 1815, there were setbacks. Democracy seldom develops in a linear way, but in waves, and democratisation takes a long time. It is also never completed.

The new state

Among the innovations was a primitive form of political parties. Their programmes were very basic. But they included modern, progressive positions.

There were democrats, who at the time were called patriots. They were unconditional supporters of France. There were also republicans who were mostly wealthy people who were in favour of France, but against paying taxes to the neighbours. In addition there were federalists, who wanted to reverse any revolutionary innovations.

While a coalition of European powers waged war against France, there were four coups d’état in Switzerland. These shifted political power from the democrats to the federalists. Eventually the French secured power for the republicans.

Another innovation was a capital city. But this took quite a journey, moving from Aarau to Lucerne and Bern before ending up in Lausanne (see the box below).

Stalled reforms

Many reforms to create a civilised, bourgeois state during the Helvetic Republic were initiated by France, so from the outside.

Personal freedoms were introduced. The special status of the Jews was scrapped. And torture was abolished. Forced membership of guilds also disappeared; traders and craftsmen could operate freely. Vocational schools were founded. The Swiss franc, as a single currency, was born. The assets of monasteries were seized. The peasants’ tithe, the Zehnte, was partially abolished.

But the new republic failed because of chronic financial struggles and the European war, which was partly fought on its soil. Internal disputes also played a role.

Democratic innovations

Two democratic innovations of the Helvetic Republic stand out, and they also influenced the emergence of other democracies:

In 1799, the first assemblies of active male citizens were established. These could elect the municipal authorities. And they chose electors, who in turn elected members of parliament, judges and the cantonal chamber, which oversaw the cantonal administration. The parliament elected a five-member executive. It named the ministers for administration and the president of the highest court, as well as governors.

The second experiment concerned the first national referendum. It was introduced on the occasion of the 1802 revision of the constitution. The new aspect was that there were no longer open-air assemblies: instead, secret ballots cast by individuals were counted.

But the counting process operated according to the veto principle. In this instance the votes in favour and abstentions were counted together. That meant that votes in favour exceeded rejections, even though more people had voted against the revision than for it. So the constitutional revision was adopted.

It would be fair to speak of a “steered democracy”. Democratic institutions emerged. But power – let us be under no illusion – remained in the hands of the French occupiers.

The civil war

Under the 1797 Lunéville peace treaty, the occupiers withdrew in the summer. That destabilised the republic. It resulted in the Stecklikrieg, or “War of Sticks” – an uprising of peasants brandishing pitchforks against the occupiers’ bayonets.

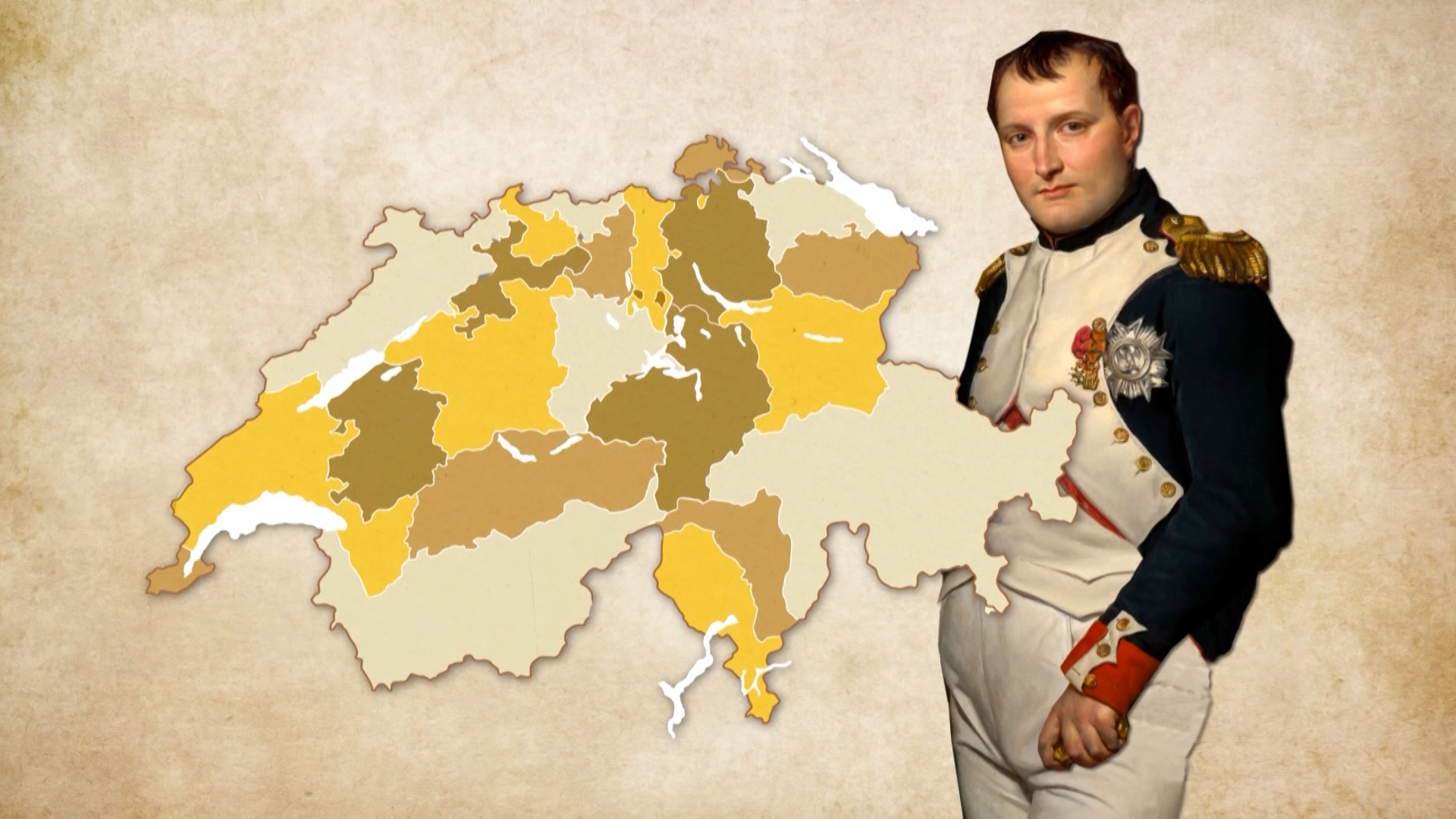

Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul of France, intervened once more and dictated a mediated constitution to the Helvetic Consulta, the assembly. It was intended to balance the interest of the fighting parties – this time, without a referendum!

A federal model was introduced, and for the first time the cantons had equal rights. In addition to the 13 core territories, there were six “Napoleonic” cantons. For them, this was liberation from their status as subjects.

After the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, Switzerland saw itself as a republic consisting of 13 sovereign republics. There was no capital.

On September 22, 1792, the French monarchy became a republic. Under its influence, model republics followed in the Netherlands (1795-1806), Italy (1797-1805) and Switzerland (1798 and 1815).

Following the French model, the Helvetic Republic got a capital in 1798. It started out as Aarau, but changed three times because of war.

In 1803, the system was changed so that the place of origin of the Landammann, the head of state, was the seat of government. Only the cantons had capitals.

In 1832, Lucerne was proposed as the permanent capital of the Swiss Confederacy, but the conservative Catholic canton rejected this proposal.

So Switzerland only got a permanent seat for parliament and government in 1848 – but this was just a Bundesstadt, or “Federal City,” and was not the administrative capital.

After France’s defeat on the battlefields, Austrian and Russian troops occupied the country. Thanks to mediation by Ioannis Kapodistrias, who later became president of Greece, an agreement was reached in 1814 to accept the Vienna Congress. That designated Geneva, Neuchâtel and Vaud as part of the Swiss Confederacy, as the country has been known since then. It resulted in the formation of a neutral buffer state with stable borders.

The Vienna Congress granted two significant exceptions to the restored confederacy: Switzerland was allowed to build a national army, and the cantons were permitted to forge Konkordats, or intercantonal treaties.

The Academic Restoration

The new state created in 1815 was in keeping with the spirit of the Restoration. This term was coined by the Bernese patrician Karl Ludwig von Haller.

He was a ruthless reactionary. A converted Catholic, he condemned any modern state ideas building on Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s “popular sovereignty” to hell. Theocracies, monarchies and military dictatorships, on the other hand, went to heaven. He also counted aristocratic republics, such as the old confederacy, among good forms of government.

But he didn’t succeed in pushing through his ideas. The young republic was already too robust.

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.