Chile looks to Switzerland as it moves to more direct democracy

The Chilean people demanded more democracy and less centralism. In drafting the new constitution, some parliamentarians looked to Switzerland as a model – although, in the eyes of some, they have gone too far.

Paulette Baeriswyl has been back in Switzerland for two months and is brimming with enthusiasm. She was part of the constitutional process in Chile and worked for a year as an adviser to Margarita Vargas, an indigenous delegate to the Constitutional Convention. During this time, the Swiss Federal Constitution was Baeriswyl’s most faithful companion.

“Chile can learn a lot from Swiss democracy,” said Baeriswyl, 38, who is doing her doctorate at the University of Zurich.

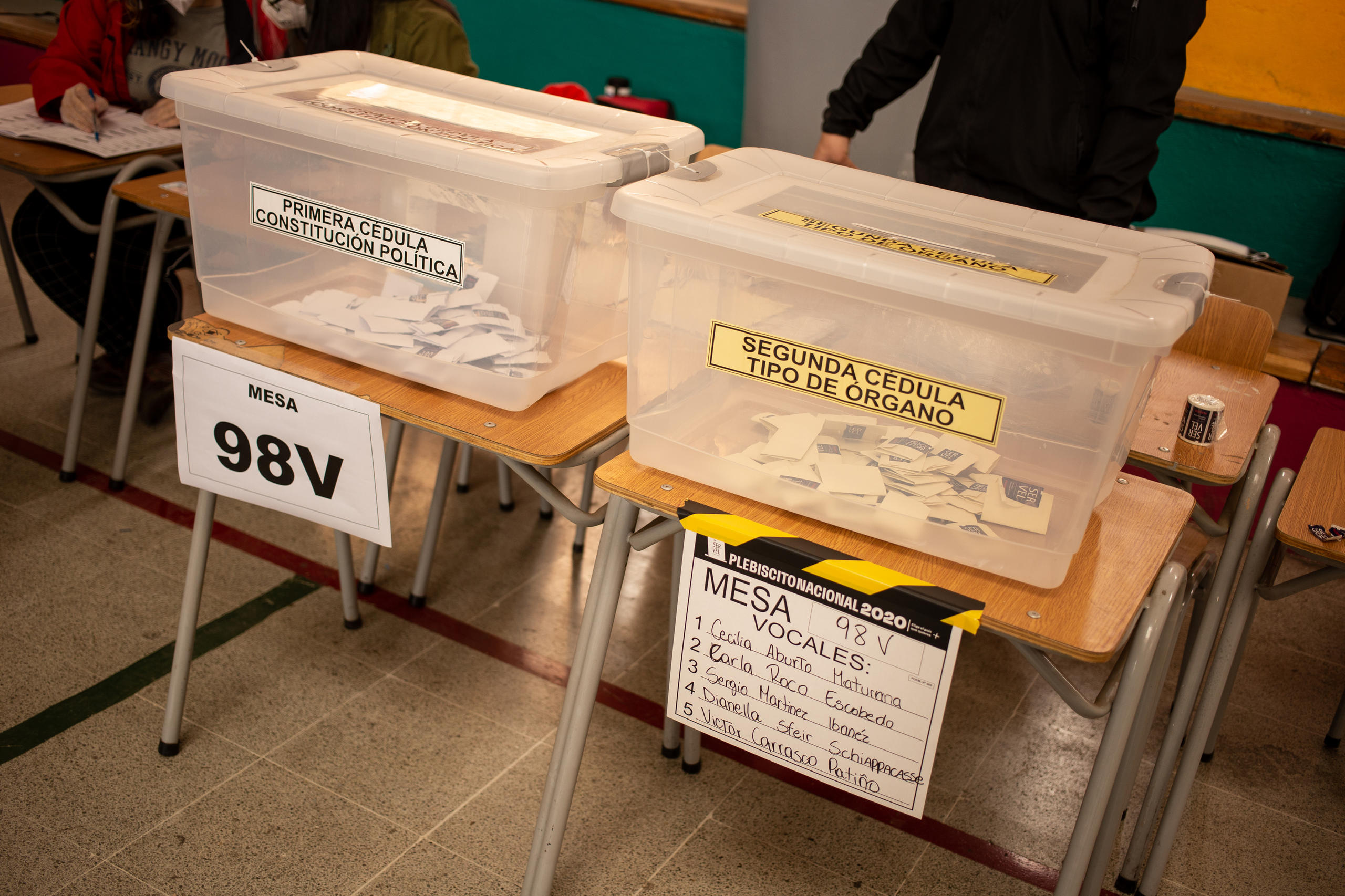

Over the past 12 months, Chile has drafted a completely new constitution. In doing so, the members of the Convention looked at different countries around the world, including Switzerland. In a referendum in October 2020, the Chilean people had tasked a specially elected Constitutional Convention with drawing up a new basic law. Many delegates were particularly concerned with strengthening democracy, decentralising the state and easing coexistence between the various indigenous peoples and Chilean majority society.

More

Chile’s constitutional vote offers window to democratic future

On September 4, 2022, the people will vote again – this time on whether to approve the new constitution. The polls predict a close outcome. Chilean law professor Javier Couso, who holds a chair at the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands, is by no means discouraged by this. “Either way, the Chilean constitutional process is a step towards more democracy. The Chilean people want more co-determination, and countries like Switzerland are a prime example of this,” he said.

Born out of the crisis

In October 2019, large swathes of the Chilean population took to the streets to protest against the right-wing government of Sebastián Piñera and the neoliberal economic system. Despite the use of massive force and human rights violations, the government was unable to stem the demonstrations.

Soon, many people were demanding a new constitution, as a way of re-founding the country with more social rights and greater democratic participation. On November 15 of the same year, a broad coalition of deputies finally decided to launch a constitutional process.

Chileans were dissatisfied with what they felt was a lack of participation in political processes, according to Couso. Electing members of parliament and the president was no longer enough. The country was also too centralised. Almost half of the population lives in the capital, Santiago, and almost all the major companies pay their taxes there, although their largest production sites are located in other parts of the country.

“People from the regions felt neglected,” Couso said. Moreover, Chile has struggled for years to resolve the conflict with its indigenous communities. They were driven from their lands long ago and their culture was suppressed.

More

Fourth of July and the reinvention of modern democracy

Instruments of direct democracy

In the eyes of its proponents, the new constitution is an attempt to fix all of this. And Switzerland was a source of inspiration in the process, said environmental activist Camila Zárate. She was elected to the Convention as a representative of the port city of Valparaíso. “Switzerland’s experience of multilingualism within one country, its federal structure and direct democracy inspired us greatly,” she said.

Meanwhile, for ideas on how to strengthen environmental protection, Chile looked to Ecuador as a model.

If the new constitution is adopted, Chileans will soon get to grips with various instruments of direct democracy, including legislative initiatives and referendums.

The country’s 16 regions are to be granted significantly more autonomy vis-à-vis the central state, and a “Chamber of Regions” is to be formed along the lines of the Swiss Senate. Regardless of their population size, the regions will be represented here with an equal number of deputies. The exact number is to be determined in an upcoming legal reform.

When Baeriswyl, who has also worked at the European Court of Human Rights, heard about the new constituent process and learnt that Margarita Vargas, a well-known representative of the Kawésqar indigenous people, had been elected to the Convention, she offered her assistance as an adviser. Vargas accepted gratefully. So Baeriswyl, who talks about her experiences in the Convention with energy and enthusiasm, put her doctoral dissertation on hold.

“For me, it was also about creating justice and being part of a process establishing a state that gives indigenous people more rights,” she said.

As a descendant of settlers and someone who has studied and travelled extensively, Baeriswyl feels she has a special responsibility. If approved, the new Chilean constitution will be the first to have been drawn up by democratically elected representatives.

Not everyone is happy

According to the latest polls, however, at least 40% of the population will vote against the new constitution. Many opponents fear that the provisions promoting expansion of the welfare state go too far. The liberal current affairs magazine The Economist wrote of a “wish list” by left-wing politicians that could not be funded by the national budget.

Critics also target the length of the constitution, which, with its 388 articles, is particularly comprehensive by international standards. “Since the right-wing parties were unable to form a blocking minority in the Convention, it pretty soon became clear that they would reject the new constitution,” said law professor Javier Couso.

The new basic law’s feminist and indigenous characteristics have also taken some parts of a still conservative society by surprise.

“The left-wing majority has imposed a constitution on the rest of the population,” Christian Democrat politician Ximena Rincón decried on a Chilean talkshowExternal link. She sees the draft constitution as a form of “revenge” that cannot possibly lead to more consensus and dialogue.

The changes in the new constitution also go too far for many descendants of Swiss settlers. Many still live on indigenous territories, where they are sometimes threatened by militant groups. From time to time they are the subject of arson attacks, with occasional fatalities. As Baeriswyl explained about the settlers: “They tend to be conservative and are afraid of losing their privileges.” They would do better, in her view, to learn from the democratisation process under way in Europe over the past 70 years.

Divided society

Chilean society is extremely divided, and the debate about the new constitution is emotionally charged. It is still unclear whether the elements of direct democracy will bring about more political stability, despite the lack of will for consensus-oriented politics and a government built on the basis of concordance.

The opponents of the new constitution are hoping it will be rejected on September 4. Their plan is for a commission of experts to write a second draft after the vote.

Meanwhile it is clear to Camila Zárate, the constitutional delegate from Valparaíso, that the Chilean people want more co-determination. “I have never seen so much interest in a political process,” she said. She is confident that the new constitution will be adopted.

If Baeriswyl had her way, Switzerland should also be taken as a model for media diversity, because “a functioning democracy also requires pluralism in the media, and that doesn’t exist in Chile at the moment”. The major newspapers and television channels in Chile are owned by right-wing entrepreneurs who are currently campaigning more or less openly for the new constitution to be rejected.

Correction: A previous version of this article said Paulette Baeriswyl lectured in law. This is not the case.

Adapted from German by Julia Bassam/ts

More

‘Chile lacks Switzerland’s democracy’

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.